Understanding the Costs of a California Irrevocable Trust

Discover the costs of an irrevocable trust in California, from setup fees to tax implications, plus detailed descriptions of types like ILITs, CRTs, and SNTs. Learn what fits your estate plan.

Estate planning plays a crucial role in safeguarding assets, providing for loved ones, and minimizing tax obligations, especially in a state like California with its unique legal landscape. One of the most potent tools available is the irrevocable trust, a permanent arrangement that distinguishes itself from revocable trusts by locking in the grantor’s decisions. This permanence delivers powerful advantages, such as asset protection and significant tax benefits, but it demands careful consideration of the associated costs and complexities.

In this extensive guide, we’ll dive into the costs of an irrevocable trust in California, covering everything from initial setup fees to ongoing administration expenses and tax implications. Following that, we’ll explore the different types of irrevocable trusts available, including Charitable Remainder Trusts (CRTs), Special Needs Trusts (SNTs), and more, to help you determine the best fit for your estate planning needs. Whether you’re just starting to explore trusts or refining an existing strategy, this blog provides practical insights tailored to California law as of March 11, 2025.

What Are the Costs of an Irrevocable Trust in California?

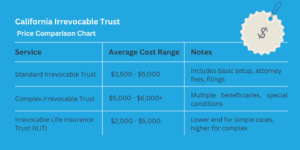

Setting up an irrevocable trust in Southern California typically involves attorney fees, which in our market analysis for Southern California showed an average range between $3,500 to $6,000 for standard cases. This cost can increase for more complex trusts, such as those involving multiple beneficiaries or special conditions like asset protection. The evidence leans toward higher fees in urban areas like Los Angeles, where the cost of living and attorney rates are elevated, potentially pushing costs toward the upper end of the range.

Factors Influencing Costs

Several factors influence the cost of setting up an irrevocable trust in Southern California:

- Complexity of the Trust: Trusts with multiple beneficiaries, unique assets, or special conditions (e.g., special needs trusts, charitable remainder trusts) increase costs, potentially pushing fees above $6,000.

- Attorney Experience: Firms with certified specialists or long-standing reputations, such as those in NAELA or ACTEC, may charge higher rates, reflecting their expertise.

- Geographic Location: Urban areas like Los Angeles and Orange County have higher attorney fees due to elevated living costs, while suburban or rural areas might offer lower rates.

- Additional Services: Costs may include notary fees ($15 per signature), filing fees ($20-$100), and appraisals for real estate or valuables ($300-$500 per asset), adding to the total.

We researched numerous Southern California law firms to ascertain the average costs for an irrevocable trust. One caveat is that many law firms do not publish their fee structures. Here at Atlantis Law Firm, for example, we do not publish our fee structures because each family and estate is different and may have varying needs which can increase or decrease the costs.

That said, here is a table reflecting our evaluation of the average costs for setting up an irrevocable trust in California:

1. Setup Costs for an Irrevocable Trust

Creating an irrevocable trust requires an initial investment, largely driven by professional services and legal necessities. The most substantial expense comes from hiring an experienced estate planning attorney. In California, attorney fees for drafting an irrevocable trust typically range from $2,000 to $10,000 or more, depending on the trust’s intricacy. For instance, a straightforward Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT) might cost around $2,000, whereas a more elaborate trust designed for tax avoidance or special needs planning could easily exceed $10,000. Attorneys in urban hubs like Los Angeles or San Francisco often charge hourly rates between $250 and $600, though some offer flat fees for standard trust documents.

Additional setup costs include notarization and, in some cases, filing with local authorities. Notary fees in California are set at $15 per signature, a small but essential expense, while recording fees, if required, can range from $20 to $100 depending on the county. If the trust involves real estate or valuable personal property like art or jewelry, appraisals become necessary to establish fair market value for tax purposes or proper funding. These appraisals generally start at $300 to $500 per asset, with more complex properties commanding higher fees. Finally, funding the trust—transferring assets into it—may incur costs such as title transfer fees for real estate, typically between $100 and $500, or expenses related to re-titling financial accounts.

2. Ongoing Administration Costs

Once an irrevocable trust is established, maintaining it generates recurring expenses that ensure its proper management. A trustee, whether a family member, professional fiduciary, or corporate entity like a bank, oversees the trust’s administration. Professional trustees in California typically charge between 0.5% and 1.5% of the trust’s assets annually. For a trust valued at $1 million, this translates to $5,000 to $15,000 per year, though corporate trustees often impose minimum fees, such as $5,000 annually, even for smaller trusts.

Accounting and tax preparation represent another ongoing cost. Irrevocable trusts are separate taxable entities requiring IRS Form 1041 for income tax returns, and hiring a CPA or tax professional to handle these filings can cost between $500 and $2,000 annually, depending on the trust’s income and complexity. If the trust holds investments like stocks or mutual funds, a financial advisor may be brought on to manage the portfolio, with fees typically ranging from 0.5% to 1% of assets under management each year. Although irrevocable trusts are designed to be permanent, certain modifications—such as decanting to a new trust or seeking court approval for changes—may occasionally be possible under California law, and these legal proceedings can cost thousands of dollars depending on the circumstances.

3. Tax Implications of Irrevocable Trusts

While not a direct expense in the traditional sense, the tax consequences of an irrevocable trust significantly influence its overall financial impact. Transferring assets into the trust is considered a gift under federal tax law. In 2025, the federal gift tax exemption stands at $13.61 million per individual, adjusted annually for inflation, with a 40% tax rate applied to amounts exceeding this threshold. California, notably, does not impose a state gift tax, which simplifies the equation for residents.

Income generated by the trust faces taxation at compressed federal trust rates, which reach 37% at just $14,450 of income in 2025, a much steeper curve than individual tax brackets. However, distributions to beneficiaries shift the tax burden to them, often at lower personal rates. One of the primary benefits of an irrevocable trust is its ability to remove assets from the grantor’s taxable estate, potentially saving substantial federal estate taxes—up to 40% on estates exceeding $13.61 million in 2025. Since California does not levy a state estate tax, this advantage applies solely to federal obligations.

Several factors drive these costs. A small trust with $100,000 in cash will incur lower fees than a $5 million trust holding real estate and business interests. Trusts designed for Medi-Cal planning or special needs support often require additional legal work, increasing setup expenses. Geographic location also plays a role, with grantors in high-cost areas like Silicon Valley or Orange County typically facing steeper professional fees than those in rural parts of the state.

Types of Irrevocable Trusts in California

California offers a variety of irrevocable trusts, each crafted to address specific estate planning goals. Below, we explore the most common types, their purposes, and key characteristics to provide a clear picture of your options.

1. Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT)

An Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT) is a type of trust specifically designed to hold a life insurance policy, with the primary goal of removing the policy’s death benefit from the grantor’s taxable estate. Once established, an ILIT cannot be altered or revoked—hence the term “irrevocable”—and it is managed by a trustee who oversees the trust according to its terms. This estate planning tool is commonly used to reduce estate taxes, provide liquidity for heirs, and ensure that the proceeds of the life insurance policy are distributed as intended, often in a controlled or protected manner. If you want 5 benefits of an ILIT check out our article on Irrevocable Life Insurance Trusts.

How It Works

The process begins when the grantor creates the ILIT and transfers ownership of an existing life insurance policy into it or has the trust purchase a new policy. By relinquishing ownership, the grantor gives up all control over the policy, such as the ability to change beneficiaries or borrow against it. The trustee, who can be a family member, friend, or professional fiduciary, manages the trust and ensures premiums are paid, typically using funds gifted to the trust by the grantor. When the grantor dies, the life insurance payout goes directly to the trust, bypassing the estate, and the trustee distributes the proceeds to the beneficiaries according to the trust’s instructions.

To fund premium payments without triggering gift taxes, the grantor can make annual gifts to the trust, leveraging the federal annual gift tax exclusion, which is $19,000 per beneficiary in 2025 (up from $18,000 in 2024). To qualify for this exclusion, the trust often incorporates “Crummey powers,” allowing beneficiaries a limited window—usually 30 days—to withdraw the gifted amount, though they typically do not, ensuring the funds remain available for premiums.

Key Features and Tax Implications

One of the standout features of an ILIT is its ability to exclude the life insurance proceeds from the grantor’s estate for federal estate tax purposes. In 2025, the federal estate tax exemption is $13.61 million per individual, with a 40% tax rate applied to amounts above that threshold. For example, if a grantor has a $10 million estate and a $5 million life insurance policy, including the policy in the estate would push the taxable value to $15 million, incurring significant taxes. By placing the policy in an ILIT, the taxable estate remains at $10 million, potentially avoiding taxes altogether if below the exemption.

However, there’s an important caveat known as the three-year rule. If the grantor transfers an existing policy to the ILIT and dies within three years, the proceeds may still be included in the estate for tax purposes, negating the tax benefit. This rule doesn’t apply if the trust purchases a new policy, making it a strategic option for those who can qualify for new coverage. California, where no state estate tax exists, amplifies the focus on federal tax savings, though community property laws may require spousal consent for funding in some cases.

2. Charitable Remainder Trust (CRT)

A Charitable Remainder Trust (CRT) is an irrevocable trust designed to provide income to the grantor or other designated beneficiaries for a specified period, after which the remaining assets are donated to one or more charitable organizations. It serves as a powerful estate planning tool that combines financial benefits for the grantor—such as income and tax advantages—with a commitment to philanthropy. Once established, a CRT cannot be altered or revoked, locking in its terms and ensuring the charitable outcome.

How It Works

The process begins when the grantor transfers assets—such as cash, securities, real estate, or other appreciated property—into the CRT. The trust then generates income, which is paid to the grantor or other named beneficiaries (e.g., a spouse or children) either for a fixed term (up to 20 years) or for the lifetime of the beneficiaries. The income can be structured as a fixed annuity (Charitable Remainder Annuity Trust, or CRAT) or a percentage of the trust’s annually revalued assets (Charitable Remainder Unitrust, or CRUT). Once the income period ends, the remaining assets, known as the “remainder,” pass to the designated charity or charities.

The grantor selects a trustee—often themselves, a family member, or a professional fiduciary—to manage the trust, invest its assets, and distribute payments. The trustee must ensure compliance with IRS rules, such as maintaining a minimum 10% remainder value for the charity, calculated at the trust’s creation.

Key Features and Tax Implications

A CRT offers several tax benefits, making it attractive for estate planning as of March 11, 2025. First, the grantor receives an immediate income tax deduction based on the present value of the charitable remainder, determined by factors like the payout rate, term, and IRS discount rates. For example, transferring $1 million into a CRT with a 5% annual payout for 10 years might yield a deduction of $300,000 to $400,000, depending on interest rates and actuarial tables.

Second, a CRT can avoid capital gains tax on appreciated assets. If the grantor contributes stock purchased for $100,000 now worth $500,000, selling it outside the trust would trigger a capital gains tax on the $400,000 gain (up to 20% federally, plus California’s 13.3% state tax). Inside the CRT, the trustee can sell the asset tax-free, reinvesting the full $500,000 to generate income, enhancing the trust’s value.

Third, the assets placed in the CRT are removed from the grantor’s taxable estate, reducing potential estate taxes. With the 2025 federal estate tax exemption at $13.61 million and a 40% rate on excess amounts, this can be significant for high-net-worth individuals. California, lacking a state estate tax, focuses the benefit on federal savings.

3. Charitable Lead Trust (CLT)

A Charitable Lead Trust (CLT) is an irrevocable trust designed to provide income to one or more charitable organizations for a specified period, after which the remaining assets pass to non-charitable beneficiaries, typically family members or heirs. It serves as an estate planning tool that reverses the structure of a Charitable Remainder Trust (CRT), prioritizing charitable giving upfront while preserving wealth for future generations. Once established, a CLT cannot be altered or revoked, locking in its terms and ensuring both its charitable and family-oriented outcomes.

How It Works

The process starts when the grantor transfers assets—such as cash, securities, or real estate—into the CLT. The trust then pays an income stream to the designated charity or charities for a set term, which can be a fixed number of years (e.g., 10 or 20) or the lifetime of the grantor or another individual. This payment can be structured as a fixed annuity (Charitable Lead Annuity Trust, or CLAT) or a percentage of the trust’s annually revalued assets (Charitable Lead Unitrust, or CLUT). After the charitable term ends, the remaining assets, known as the “remainder,” are distributed to the non-charitable beneficiaries, such as the grantor’s children or grandchildren.

A trustee—often the grantor, a family member, or a professional fiduciary—manages the trust, invests its assets, and ensures payments are made to the charity. The trustee must comply with IRS regulations, such as ensuring the trust’s design meets tax-advantaged requirements.

Key Features and Tax Implications

A CLT offers distinct tax benefits, making it a valuable tool as of March 11, 2025. Unlike a CRT, the grantor does not typically receive an immediate income tax deduction unless the trust is structured as a “grantor trust,” where the grantor retains certain control (e.g., the right to substitute assets), subjecting them to income tax on trust earnings. In a non-grantor CLT, the more common form, the trust itself is taxed as a separate entity, and the charitable payments may generate a deduction for the trust, not the grantor.

The primary tax advantage lies in gift and estate tax savings. When assets are placed in the CLT, their transfer to the trust is treated as a taxable gift to the remainder beneficiaries (e.g., heirs), but the value of that gift is reduced by the present value of the charitable payments, calculated using IRS discount rates. For example, transferring $1 million into a CLAT paying $50,000 annually to charity for 10 years might result in a taxable gift of only $500,000 to heirs, depending on rates and terms. This can significantly lower or eliminate gift taxes, leveraging the 2025 annual gift tax exclusion ($19,000 per beneficiary) and lifetime exemption ($13.61 million).

Additionally, the assets in the CLT are removed from the grantor’s taxable estate, reducing potential estate taxes (40% on amounts over $13.61 million in 2025). If the trust’s investments grow beyond the IRS-assumed rate (the “7520 rate”), that excess growth passes to heirs tax-free, amplifying wealth transfer—a strategy known as a “zeroed-out CLAT.”

4. Special Needs Trust (SNT)

A Special Needs Trust (SNT) is an irrevocable trust designed to provide financial support for an individual with disabilities without jeopardizing their eligibility for government benefits, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid program). It allows the grantor—often a parent, grandparent, or guardian—to set aside assets to enhance the quality of life for a disabled beneficiary, covering expenses beyond what public assistance provides, while ensuring those assets don’t count against strict income and resource limits. Once established, an SNT cannot be altered or revoked, locking in its protective structure.

How It Works

The process begins when the grantor creates the SNT and funds it with assets, such as cash, investments, real estate, or life insurance proceeds. A trustee—typically a family member, friend, or professional fiduciary—is appointed to manage the trust and distribute funds for the benefit of the disabled individual, known as the beneficiary. These distributions cover “supplemental” needs, like education, therapy, transportation, or recreational activities, rather than basic necessities (e.g., food and shelter) that could replace government aid and trigger ineligibility.

The trust’s terms dictate how and when funds are used, tailored to the beneficiary’s needs and circumstances. Upon the beneficiary’s death, the trust may direct remaining assets to other family members or, in some cases, repay the state for Medicaid benefits received, depending on the SNT type.

5. Qualified Personal Residence Trust (QPRT)

A Qualified Personal Residence Trust (QPRT) is an irrevocable trust designed to transfer ownership of a primary or vacation home out of the grantor’s taxable estate at a reduced gift tax value, ultimately passing it to beneficiaries such as children or heirs. It’s a specialized estate planning tool that leverages IRS rules to minimize gift and estate taxes while allowing the grantor to continue living in the property for a set period. Once established, a QPRT cannot be altered or revoked, locking in its terms and tax benefits.

How It Works

The process starts when the grantor transfers a residence—either their primary home or a vacation property—into the QPRT. The trust is set up for a fixed term, typically 5, 10, or 15 years, during which the grantor retains the right to live in the home rent-free. This term is a critical component, as it determines the taxable gift value and the trust’s success. At the end of the term, ownership of the property passes to the beneficiaries (e.g., children), and the grantor must vacate or pay fair market rent to continue living there, depending on family arrangements.

A trustee—often the grantor, a family member, or a professional fiduciary—manages the trust, ensuring compliance with IRS requirements, such as limiting the trust to one personal residence (or a share of one) and prohibiting its sale back to the grantor. The home’s value is frozen for gift tax purposes at the time of transfer, discounted by the value of the grantor’s retained living rights, calculated using IRS Section 7520 interest rates.

Key Features and Tax Implications

The QPRT’s primary tax benefit is reducing gift tax liability. When the home is transferred, the grantor makes a taxable gift to the beneficiaries, but its value is discounted based on the term and IRS rates. For example, in March 2025, with a $1 million home and a 10-year term at a 3% 7520 rate, the taxable gift might be $600,000, not the full $1 million, leveraging the 2025 annual gift tax exclusion ($19,000 per beneficiary) and lifetime exemption ($13.61 million). If the home appreciates to $1.5 million by the term’s end, that $900,000 growth passes to heirs tax-free.

The trust also removes the property from the grantor’s taxable estate, lowering potential estate taxes (40% on amounts over $13.61 million in 2025). However, a critical risk exists: if the grantor dies before the term ends, the home’s full value at death reverts to their estate, negating tax benefits and subjecting it to estate tax. This makes the QPRT a calculated gamble, best for those confident in outliving the term.

6. Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT)

A Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT) is an irrevocable trust designed to transfer appreciating assets to beneficiaries, typically heirs, with minimal or no gift tax liability, while allowing the grantor to receive a fixed income stream for a specified term. It’s a sophisticated estate planning tool that leverages IRS rules to “freeze” the value of transferred assets for tax purposes, passing future growth tax-free to the next generation. Once established, a GRAT cannot be altered or revoked, locking in its structure and tax advantages.

How It Works

The process begins when the grantor places assets—often high-growth stocks, real estate, or business interests—into the GRAT. The trust is set for a fixed term, typically 2 to 10 years, during which the grantor receives an annual annuity payment, calculated as a fixed percentage of the initial asset value. At the end of the term, any remaining assets pass to the beneficiaries (e.g., children), and the grantor’s involvement ends.

A trustee—often the grantor, a family member, or a professional fiduciary—manages the trust, ensuring annuity payments and compliance with IRS requirements. The annuity is determined using the IRS Section 7520 interest rate (the “hurdle rate”), which assumes a modest growth rate for the assets. If the assets outperform this rate, the excess growth transfers to beneficiaries tax-free.

Key Features and Tax Implications

The GRAT’s primary tax benefit is reducing gift tax liability. When assets are transferred into the trust, the grantor makes a taxable gift to the beneficiaries, but its value is discounted by the present value of the annuity payments the grantor retains, calculated using the 7520 rate. In a “zeroed-out GRAT,” the annuity is set so the retained value equals the initial contribution, reducing the taxable gift to near zero. For example, in March 2025, with a $1 million GRAT, a 2-year term, and a 3% 7520 rate, an annuity of $515,000 annually might zero out the gift, fitting within the $19,000 annual exclusion or $13.61 million lifetime exemption.

The trust also shifts future appreciation out of the grantor’s taxable estate, lowering potential estate taxes (40% on amounts over $13.61 million in 2025). If the $1 million grows to $1.5 million over 2 years at 22% annually, the $500,000 excess passes to heirs tax-free, assuming the grantor survives the term. However, if the grantor dies during the term, the trust assets revert to their estate, potentially subjecting them to estate tax and negating the strategy.

As a grantor trust, the grantor pays income tax on trust earnings, even if not distributed, preserving the principal for beneficiaries and further reducing the estate by the tax paid—a hidden benefit.

7. Dynasty Trust

A Dynasty Trust is an irrevocable trust designed to preserve and transfer wealth across multiple generations—potentially lasting for decades or even centuries—while minimizing or avoiding estate, gift, and generation-skipping transfer (GST) taxes at each generational shift. It allows the grantor to provide for their children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and beyond, maintaining assets in a protected structure managed by a trustee. Once established, a Dynasty Trust cannot be altered or revoked, ensuring its longevity and tax advantages.

How It Works

The process begins when the grantor funds the trust with assets—such as cash, investments, real estate, or business interests—typically up to the federal estate and GST tax exemption amount, which is $13.61 million per individual in 2025. The trust is structured to benefit successive generations, with a trustee—often a professional fiduciary or institution—managing the assets and distributing funds according to the grantor’s instructions. These distributions can be for specific purposes (e.g., education, health) or at the trustee’s discretion, balancing support with preservation.

The trust’s duration is governed by the state’s Rule Against Perpetuities, which limits how long a trust can last. Many states, like California, traditionally allow trusts to endure for about 90 years after creation or 21 years after the death of a named beneficiary. However, some states (e.g., Nevada, Delaware) have abolished or extended this rule, permitting “perpetual” Dynasty Trusts lasting hundreds of years. California grantors can establish trusts in such states to maximize longevity, though local law may influence administration.

Key Features and Tax Implications

The Dynasty Trust’s standout feature is its ability to avoid transfer taxes across generations. Normally, assets passed to children face estate tax (40% over $13.61 million in 2025), and those skipped to grandchildren incur GST tax (also 40% over the exemption). A Dynasty Trust allocates the grantor’s GST exemption at creation, shielding assets and their growth from these taxes indefinitely. For example, $10 million funded in 2025 could grow to $50 million over decades, passing tax-free to descendants if properly structured.

The initial transfer is a taxable gift, but the 2025 lifetime gift tax exemption ($13.61 million) often covers it without tax liability. Annual gifts ($19,000 per beneficiary) can further fund the trust tax-free. Income generated within the trust is taxed—either to the trust at compressed rates (37% at $14,450 in 2025) or to beneficiaries if distributed—but the principal and growth escape transfer taxes, a key distinction.

Assets in the trust are removed from the grantor’s taxable estate, reducing estate tax exposure. In California, with no state estate tax, this focuses savings on federal taxes, though community property rules may require spousal consent for funding.

8. Medi-Cal Asset Protection Trust

A Medi-Cal Asset Protection Trust is an irrevocable trust designed to shield assets from being counted toward Medi-Cal eligibility and recovery rules in California, enabling the grantor to qualify for long-term care benefits while preserving wealth for heirs. It’s a strategic estate planning tool for individuals anticipating the need for Medi-Cal—California’s Medicaid program—to cover nursing home or in-home care costs, which can exceed $100,000 annually. Once established, the trust cannot be altered or revoked, ensuring its protective structure aligns with Medi-Cal’s stringent requirements.

How It Works

The process starts when the grantor transfers assets—such as a home, cash, or investments—into the Medi-Cal Asset Protection Trust. A trustee, typically a trusted family member or professional fiduciary, manages the trust and its assets, ensuring they’re no longer considered the grantor’s property for Medi-Cal purposes. The grantor can retain certain rights, like living in the home if it’s included, but relinquishes control over the assets’ ultimate disposition.

Medi-Cal imposes a look-back period of 30 months (2.5 years) for asset transfers as of March 11, 2025. Assets moved into the trust at least 30 months before applying for Medi-Cal are exempt from eligibility calculations, which cap countable resources at $2,000 for an individual ($3,000 for a couple, with adjustments for a community spouse). After the grantor’s death, the trust can distribute remaining assets to beneficiaries (e.g., children), potentially avoiding Medi-Cal’s estate recovery process, where the state seeks reimbursement from the deceased’s estate for care costs.

Key Features and Legal Implications

The trust’s primary feature is asset exemption. By placing assets in an irrevocable trust before the look-back period, they’re excluded from Medi-Cal’s resource limit, allowing eligibility without spending down wealth. For example, a $500,000 home transferred in 2025 won’t count toward the $2,000 limit if Medi-Cal is sought in 2028. The grantor can often retain a life estate in the home, preserving the right to live there, though this may trigger recovery unless structured carefully.

Another key aspect is recovery avoidance. Medi-Cal can recover costs from an estate after death, targeting assets like the home, but a properly designed trust can bypass this by ensuring assets aren’t in the probate estate. However, if the trust retains benefits for the grantor (e.g., income), recovery may still apply to those distributions, requiring precise drafting.

The trust doesn’t directly reduce federal estate taxes (40% over $13.61 million in 2025), as California has no state estate tax, but it aligns with Medi-Cal’s focus on resource limits rather than tax savings. Income from trust assets may be taxable to the grantor or trust, depending on its structure (grantor vs. non-grantor trust).

Comparing Costs and Benefits of Irrevocable Trusts

Each type of irrevocable trust balances costs against its unique advantages, depending on the grantor’s goals and estate size. An ILIT, with its relatively low setup cost, delivers substantial estate tax savings for modest estates with life insurance policies. A dynasty trust, though expensive to establish and maintain, maximizes generational wealth for high-net-worth individuals. Meanwhile, an SNT prioritizes quality of life for a disabled loved one, with its moderate costs offset by preserved public benefits. For a $10 million estate, a $5,000 setup fee might seem negligible, but for a $200,000 estate, it could feel prohibitive, highlighting the importance of aligning costs with financial capacity.

California-Specific Considerations

California’s legal framework introduces specific nuances to irrevocable trusts. Community property rules mean spouses must consider joint ownership when funding trusts, potentially requiring spousal consent or separate property agreements. Trusts also sidestep California’s probate process, which can cost 4% to 7% of an estate’s value, offering significant indirect savings. For Medi-Cal planning, compliance with strict state and federal regulations adds complexity, particularly for asset protection trusts.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Irrevocable Trust in California

Irrevocable trusts in California provide robust solutions for tax savings, asset protection, and tailored estate planning, but they come with notable costs. Setup fees typically range from $2,000 to $10,000 or more, while ongoing expenses hinge on the trust’s size and purpose. Tax implications, such as estate tax savings, often justify the investment for those with substantial assets. Whether you’re considering an ILIT, CRT, SNT, or another type, selecting the right trust requires aligning it with your personal and financial objectives. Consulting a California estate planning attorney is essential to navigate these options and ensure your legacy is secure. Ready to take the next step? Contact us today to set up a free consultation.

About Atlantis Law: Atlantis Law focuses its practice on protecting the people you care about. Led by James Long a trust and business lawyer with over a decade of experience, Atlantis Law provides quality representation at affordable and flexible rates. We help protect your children and other loved ones through comprehensive estate planning, business planning, contract drafting, and (if necessary) aggressive litigation or dispute resolution. Our clients are not just numbers on a page but extended members of our own family. Feel free to call of to set up a free consultation (951) 228-9979, or email claudia@atlantislaw.com, and see how you can become part of our Atlantis Law Family! We serve all areas of Southern California, including Eastvale, Ontario, Rancho Cucamonga, Chino, Chino Hills, Corona, Fontana, Redlands, Loma Linda, and San Bernardino.

Disclaimer: Nothing in this post is intended to be legal advice to you or for a particular situation. Nothing in this post creates any kind of lawyer-client relationship. All legal cases are different and typically hinge on a complex set of varied factors. Therefore, if you think that your legal rights have been violated or that you need an attorney, please do not rely solely on this post for your legal advice. Consult with a lawyer immediately, or call Atlantis Law at (951) 228-9979 to see if we can represent you.